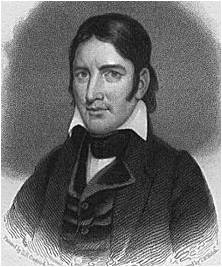

Colonel David Crockett

(1786-1836)

Colonel David Crockett (17th August 1786 – 6th March 1836) was a lionized American national hero, patriot, soldier and politician in the 19th century. He was just referred to as Davy Crockett many times. He stood for Tennessee in the American House of Representatives, he did military service in the Texas revolution, and he died in the Alamo battle at the age of 49.

Davy Crockett (originally David de Crocketagne) was born in Greene County, Tennessee, near the river Nolichucky. Among his ancestors we can find the French Huguenots who settled down in Cork, Ireland, and later moved to Donegal. His grandparents emigrated to America, and according to the traditions, his father was born in the open sea, during the voyage.

David was the 5th among 9 children, his parents were John and Rebecca Hawkins Crockett. David got his name from his grandfather who was killed by redskins at his home in Rogersville, Tennessee.

According to Crockett’s own words, his childhood was full of adventures, difficulties and travelling; he said that he had killed a bear at the age of 3.

Soon after going to school Crockett left home to get rid of his father’s thrashing. Crockett recalled that he had fell out with a brawling school-boy who humbled him on the first school-day, and he wanted to escape his strict teacher’s thrashing so he became truant. Some weeks later the teacher called Crockett’s father to account why his son didn’t take lessons. The young Davy explained the situation, but his father was evidently angry because the money spent on his son’s education became wasted and useless. He wasn’t interested in his son’s point of view at all. Then Crockett left home to escape another thrashing, and he was just wandering from city to city for years. During this time he visited almost every city and village in Tennessee and learned hunting, deforestation and fur-hunting.

After wandering of many years, around his 19th birthday Crockett turned home unexpectedly. While he was away, his father opened a pub, and Crockett had a rest there. Nobody recognized him but his little sister who was glad of him. To his great surprise, the whole family, including his father was very happy to see and welcome him again.

Shortly after this Crockett engaged Margaret Elder, although the marriage never happened, but the contract of marriage has been kept at the Court of Dandridge, Tennessee. Crockett’s fiancée changed her mind and married someone else.

On the 12th August 1806 Crockett married Polly Finley (1788-1815). They had two sons: John Wesley and William, and a daughter Margaret. After Polly’s death David re-married. In 1816 he married a widow, Elizabeth Patton who gave birth to another 3 children: Robert, Rebeckah and Matilda. On the 24th September 1813 he entered the Second Regiment of the Tennessee Voluntary Shooters, and as an active warrior he served 90 days long under Colonel John Coffee in the Creek battle on the area of present-day Alabama. He was relieved of military service on the 27th March 1815. Later (27 March 1818) he was voted to lieutenant-colonel in the 57th Regiment of the Tennessee Militia.

On the 17th September 1821 Crockett was elected to the Committee of Problems and Complaints, and to the House of Representatives of the US in 1826 and 1828. As a representative, he supported the new settlers’ rights who were kept within limits in buying land in the west if they had no properties earlier. Crockett was opposed to President Andrew Jackson’s redskin-relocation plans, and this conflict caused that he lost his re-election in 1830. But he won in 1832 when he re-entered for the representation of Tennessee.

Crockett was immovably against the government’s lavish spending. In his speech (Not yours to give) he criticized his congressional colleagues who wanted to give a grant to a navy-widow from state revenue, but they weren’t ready to devote even their one week’s salary for the cause. He thought that lavish spending was “anti-constitutional”, but the popular motion died in the congress, thanks to that speech.

His autobiographical book was published in 1834, with the title “The story of David Crockett’s life”. Crockett went east to make his book popular, and with a close vote he was beaten in re-election. In 1835 he lost again. Then he said: “I told the people in my zone that I would serve them with the same loyalty as so far, but if they don’t need it… then let them go to hell, and I will go to Texas.” So did he, and joined the Texas revolution.

On the 31st October 1835 Crockett left Tennessee for Texas, as he wrote: “I want to range over Texas thoroughly before turning back.” He went along the Kawesch Glenn on a south-western pathway. Early in January 1836 he arrived to Nacogdoches, Texas. On the 14th January Crockett and his 65 mates took an oath on the caretaker Texas government before Judge John Forbes. Everyone was promised 19 square kilometers estate as payment. On the 6th February Crockett and other 5 men rode to San Antonio de Bexar and set up camp beside the city.

William Barret Travis was the commander at the time of the Alamo’s siege. Texas forces consisted of 180-260 people while the offensive Mexicans had serious numerical superiority with 2400 soldiers. Mexican commanders did know it well so they recommended free leaving to Americans. Travis rejected surrender and the whole troop agreed with him.

All that we can know about Crockett’s destiny is that he died during the Alamo’s siege. According to a report, his body was found together with 16 Mexicans and Crockett’s knife was still there in one of them.

In 1955 some controversial evidences came to light which questioned the accepted supposition about Crockett’s destiny. These are based on José Enrique de la Peña’s diary which said that there had been 6 survivors, among them Crockett as well. According to Peña’s report, Mexican General Manuel Fernández Castrillón took some prisoners in the Alamo who were executed a bit later, on the orders of the Mexican commander and president Antonio López de Santa Anna. According to Peña’s diary, Crockett was identified by Castrillón, he and another two Mexican commanders begged Santa Anna for saving the big hero’s life. Santa Anna refused them and he ordered to execute each survivor immediately.

The opponents of this assumption query its validity with two arguments. First of all with the fact that no other report but that one of Peña came to light claiming that Crockett had survived the Alamo. The Mexican government doesn’t have any documents or personal notes from those who were present at the Alamo battle that there had been any survivors among the defenders, especially not anything that would have mentioned Crockett as a survivor. Secondly, many people think that Peña’s diary was just a forgery which was made with the purpose of describing Santa Anna much more devilish than it’s done by American (and mostly by Texan) historians since the Alamo’s fall. All things considered, the most probable assumption is that Crockett died in the last minutes of the siege forced into the Alamo’s inner fortification.

According to the most sources Crockett and all the Alamo-defenders were cremated in a common grave. There were unconfirmed notes that some Mexicans charged with burning transported Crockett’s body to a secret and unsigned place to bury him there. Other sources say that his body had been transported back to Tennessee in secret lest Santa Anna should use it as a trophy.

His gravestone reads: “Davy Crockett, Pioneer, Patriot, Soldier, Trapper, Explorer, State Legislator, Congressman, martyred at The Alamo. 1786 – 1836”

One of Crockett’s phrases which was published in the chronicles between 1835 and 1856: “Be always sure you are right, then go ahead.”

The Walt Disney Studios recalled the hero’s memory, and shot a Davy Crockett series. Three biographical episodes were shown first. Because these had great popularity, several other episodes were directed later as well.

Movies in which Davy Crockett’s role was played:

Davy Crockett – In Hearts United, 1909 (silent film)

Davy Crockett, 1916 (silent film)

Davy Crockett at the fall of the Alamo, 1926 (silent film)

The Painted Stallion, 1937

Heroes of the Alamo, 1937

Man of Conquest, 1939

Davy Crockett, Indian Scout, 1950

The Man from the Alamo, 1953

The Alamo, 1960

The Alamo: Thirteen Days of Glory, 1987

Alamo: The Price of Freedom, 1988

Davy Crockett: Rainbow in the Thunder, 1988

Davy Crockett: Rainbow in the Thunder, Davy Crockett: A Natural Man, Davy Crockett: Guardian Spirit, Davy Crockett: Letter to Polly, 1988-1989

The Alamo, 2003

The True Memoirs of Davy Crocket

Page by GREYMAN

@Jesse: She is the godmother of my daughter. 🙂

@Mope: Thanks! 🙂 Beautiful legends… 😀

Very interesting person, this Davy Crockett, thank you, Greyman. Though, the episode with 16 Mexicans and a knife seems hmm… mythological. But that’s what happens with legends 🙂

Grey you took SAPE’s women? :p

I am watched that Alamo movie. Nice work Grey

Thanks Guys! 😀

Even if it is appropriate to thank someone without whom these articles were not published on the website.

THANK YOU CORNELIA!

/She is my translator/

She is my ex-wife…

Yep she is!!! 😀 😀 😀

Again nice page GREY and Sape. Again very interesting person that I didn’t know before reading the page.

I updated it: Page by GREYMAN.

@Grey: Nice page. 🙂

Thanx Biondo. 🙂

Hehe, so it is your creation, Greyman, not Sape’s one.

Nice, Sape. Long time since your (and Greyman’s) last page about Old West.

You made me remember when I was child and my brother had a typical Davy Crockett hat, that almost made me dye of envy 🙂